There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Mon Jun 30, 2025

పరిచయం:

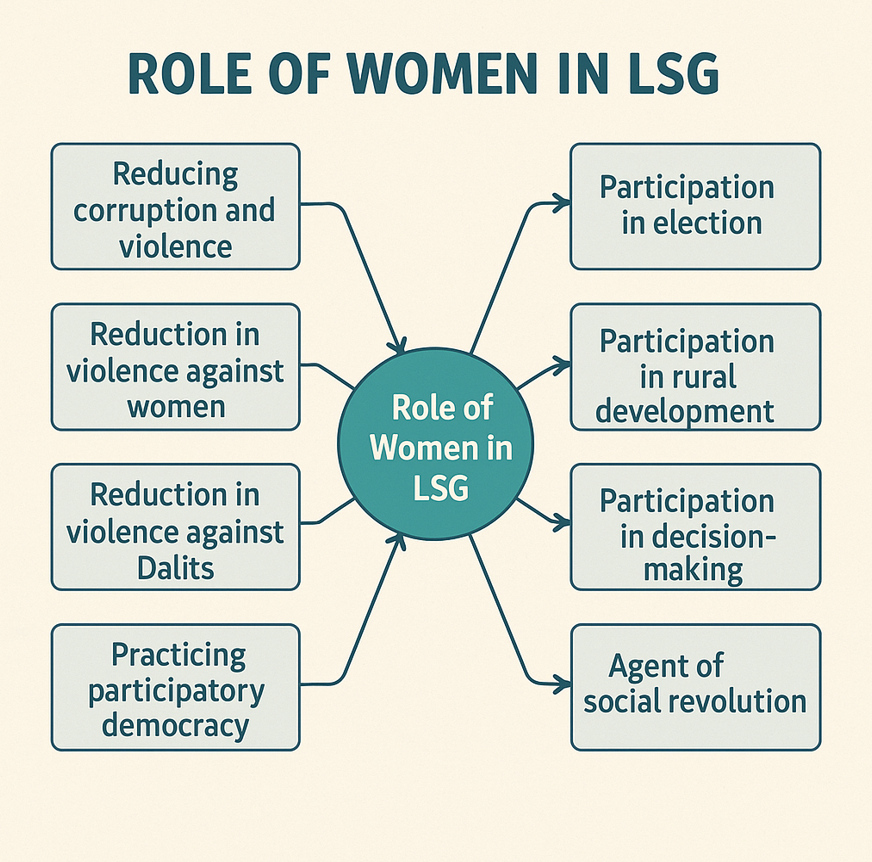

73వ మరియు 74వ రాజ్యాంగ సవరణలు స్థానిక స్వపరిపాలనలో మహిళలకు 33% రిజర్వేషన్ను తప్పనిసరి చేశాయి, దీని ఫలితంగా 2024 నాటికి 14 లక్షల మంది మహిళలు స్థానిక పరిపాలన సంస్థలలో సేవలు అందిస్తున్నారు. అయినప్పటికీ, ఈ గ్రామీణ స్థాయి సమ్మిళనం ఉన్నత స్థాయిలో ప్రతిఫలించలేదు, ఎందుకంటే 49% జనాభా ఉన్నప్పటికీ, 18వ లోక్సభలో మహిళలు కేవలం 14% సీట్లను మాత్రమే కలిగి ఉన్నారు. ఈ అంతరం భారతదేశంలో లోతుగా పాతుకుపోయిన పురుషాధిక్య రాజకీయ వ్యవస్థపై ఈ సంస్కరణల పరిమిత ప్రభావాన్ని సూచిస్తుంది.

విషయం:

రిజర్వేషన్ యొక్క సానుకూల ప్రభావాలు:

1. స్థానిక పరిపాలనలో అధిక ప్రాతినిధ్యం:

-2024 నాటికి, పంచాయతీ రాజ్ సంస్థలలో (PRIs) ఎన్నికైన ప్రతినిధులలో సుమారు 46% మంది మహిళా సర్పంచ్లు ఉన్నారు. ఇది 14 లక్షలకు పైగా మహిళలు గ్రామీణ నాయకత్వంలో ఉన్నారని సూచిస్తుంది. దీనితో భారతదేశం మహిళల స్థానిక పరిపాలన భాగస్వామ్యంలో ప్రపంచ నాయకులలో ఒకటిగా నిలిచింది.

2. అణగారిన వర్గాల ప్రవేశం:

-ఈ విధానం తక్కువ కులాలు మరియు గతంలో విస్మరించబడిన మహిళలకు అధికారికంగా రాజకీయ నిర్మాణాలలోకి ప్రవేశించే అవకాశాన్ని కల్పించింది. ఇది వారి సామాజిక మరియు రాజకీయ సాధికారతకు ఉత్ప్రేరకంగా నిలిచింది.

3. పరిపాలన ప్రాధాన్యతల పునర్నిర్మాణం:

-మహిళా నాయకులు పేదరికం, పారిశుద్ధ్యం, పోషణ, విద్య, మరియు లింగ ఆధారిత వివక్ష వంటి సమస్యలను ముందుంచారు. దీనితో సమగ్ర అభివృద్ధి ప్రణాళిక మరియు అమలు సాధ్యమైంది.

4. మెరుగైన సామీప్యత:

-ఎన్నికైన మహిళలు తరచూ అందుబాటులో ఉండడం ద్వారా పౌర-ప్రభుత్వ సంబంధాలు, ముఖ్యంగా గ్రామీణ సమాజాలలోని మహిళలకు అవకాశాలు మెరుగుపడ్డాయి.

5. ఎక్కువ పారదర్శకత మరియు జవాబుదారీతనం:

-అనుభవసిద్ధ అధ్యయనాలు మహిళల నేతృత్వంలోని పంచాయతీలు తక్కువ అవినీతి మరియు సమాజ అవసరాలకు ఎక్కువ స్పందనను ప్రదర్శిస్తాయని చూపిస్తున్నాయి.

6. సాధికారత యొక్క విస్తృత ప్రభావం:

-నాయకత్వ పాత్రలలో మహిళల అనుభవం సమాజంలో విస్తృత భాగస్వామ్యాన్ని ప్రోత్సహించడం ద్వారా మహిళలలో ఆత్మవిశ్వాసాన్ని నిర్మించింది.

పరిమిత ప్రభావం మరియు కొనసాగుతున్న పురుషాధిక్యం:

1. ప్రాతినిధ్యంలో నిలువు అంతరం:

-పంచాయతీ రాజ్ సంస్థలలో 46% కంటే ఎక్కువ ఎన్నికైన ప్రతినిధులు మహిళలైనప్పటికీ, ఈ గ్రామీణ భాగస్వామ్యం ఉన్నత స్థాయిలో ప్రతిఫలించలేదు. 18వ లోక్సభలో కేవలం 14% ఎంపీలు మహిళలు ఉన్నారు ఇది వారి 49% జనాభా వాటాతో అసమానంగా ఉంది.

2. నామమాత్ర సాధికారత:

-అనేక సందర్భాలలో, నిజమైన అధికారం పురుష బంధువుల వద్దనే ఉంటుంది. దీనితో “సర్పంచ్ పతి” అనే సాంప్రదాయం ఏర్పడింది. ఇక్కడ ఎన్నికైన మహిళలు నిర్ణయాధికారం లేకుండా నామమాత్ర అధిపతులుగా పనిచేస్తారు.

3. రాజకీయ ఇచ్ఛాశక్తి లోపం:

-మహిళల రిజర్వేషన్ బిల్ 2023లో నారీ శక్తి వందన అధినియమంగా ఆమోదించబడినప్పటికీ, 1996లో ప్రవేశపెట్టినప్పటి నుండి దాదాపు 30 సంవత్సరాల ఆలస్యం తర్వాత ఇది జరిగింది. ఇది ఉన్నత శాసనసభలలో మహిళల ప్రాతినిధ్యాన్ని నిర్ధారించడంలో రాజకీయ అయిష్టతను ప్రతిబింబిస్తుంది.

4. సాంస్కృతిక మరియు నిర్మాణాత్మక అడ్డంకులు:

-పురుషాధిక్య సామాజిక నియమాలు, గృహ బాధ్యతలు, మరియు కుటుంబ సహాయం లేకపోవడం మహిళల రాజకీయ ఆకాంక్షలను పరిమితం చేస్తున్నాయి. అంతేకాక, రాజకీయాలలో నేర మరియు పురుషాధిక్య నియమాలు విస్తృత భాగస్వామ్యాన్ని అడ్డుకుంటున్నాయి.

5. ఉన్నత వర్గ ఆధిపత్యం మరియు వంశవాద రాజకీయాలు:

-రాజకీయ ప్రవేశం తరచూ ప్రభావవంతమైన కుటుంబాల “త్రిబి బ్రిగేడ్” – బేటీ, బహూ, బీవీలకు పరిమితమై ఉంటుంది. ఈ ఉన్నత వర్గ పక్షపాతం గ్రామీణ లేదా మొదటి తరం మహిళా నాయకులను ముందుకు సాగకుండా అడ్డుకుంటుంది.

6. ఊర్ధ్వగమన ప్రభావం లోపం:

-73వ మరియు 74వ సవరణల కింద వికేంద్రీకరణ విజయం సాధించినప్పటికీ, విజయవంతమైన మహిళలను స్థానిక సంస్థల నుండి రాష్ట్ర శాసనసభలు లేదా పార్లమెంటు వంటి ఉన్నత స్థాయికి తీసుకెళ్లడానికి స్పష్టమైన సంస్థాగత విధానం లేదు.

ముందుకు వెళ్లే మార్గం:

1.సామర్థ్య నిర్మాణం:

-పంచాయతీ రాజ్ మంత్రిత్వ శాఖ–UNDP సూచించినట్లు, ఎన్నికైన మహిళా ప్రతినిధులకు శిక్షణను మెరుగుపరచాలి.

2. చట్టపరమైన రక్షణలు:

-ప్రాక్సీ పనితీరును శిక్షించడం మరియు స్వతంత్ర నిర్ణయాధికారం కోసం చట్టపరమైన రక్షణను ప్రోత్సహించడం.

3. రాజకీయ వ్యవస్థను బలోపేతం:

-స్థానిక సంస్థల నుండి రాష్ట్ర శాసనసభలు మరియు పార్లమెంటుకు సమర్థవంతమైన మహిళా నాయకులను గుర్తించి, ప్రోత్సహించే సంస్థాగత విధానాలను సృష్టించడం, మహిళల రిజర్వేషన్ చట్టం (2023) యొక్క అధికారాన్ని ఉపయోగించడం.

4. లింగ- ఆధార పరిపాలన:

-లింగ ఆడిట్లు, మెంటర్షిప్ కార్యక్రమాలు, మరియు సమాజ స్థాయిలో అవగాహనను సంస్థాగతీకరించడం ద్వారా సాంప్రదాయ భావనలను ఛేదించడం.

ముగింపు

స్థానిక రిజర్వేషన్లు మహిళలను పరిపాలనలోకి ప్రవేశించేలా చేసినప్పటికీ, పురుషాధిక్య నియమాలు నిజమైన సాధికారతను అడ్డుకుంటున్నాయి. చట్టపరమైన సంస్కరణలను సాంస్కృతిక మరియు సంస్థాగత మార్పులతో పూరకం చేయడం ద్వారా భారతదేశం ముందుకు సాగాలి. రువాండాలో 61% మహిళల పార్లమెంటు ప్రాతినిధ్యం బలమైన రాజకీయ ఇచ్ఛాశక్తి లింగ సమానత్వాన్ని పరిపాలన వాస్తవంగా మార్చగలదని చూపిస్తుంది.